by Séan M. Poole

Antonio Gattorno,

a pioneer of Cuba’s Modernist Movement, was a versatile, innovative and enigmatic artist. His masterfully executed paintings are technically superb. His iconic imagery is mysterious and oftentimes misunderstood. Gattorno’s earliest paintings laid the foundation for and became the archetype of Cuban Modernism.

Antonio Gattorno,

a pioneer of Cuba’s Modernist Movement, was a versatile, innovative and enigmatic artist. His masterfully executed paintings are technically superb. His iconic imagery is mysterious and oftentimes misunderstood. Gattorno’s earliest paintings laid the foundation for and became the archetype of Cuban Modernism.Gattorno later developed a Neo-Romantic, surrealist style inspiring many critics to compare him to Salvador Dali. To this day, these paintings are powerful, sophisticated and puzzling. They are quite frequently misinterpreted.

Emily Genauer, critic for the New York World Telegram, reviewing Gattorno’s solo exhibit at the Passedoit gallery on October 9, 1944, writes, “Gattorno is a painter of extraordinary technical skill and uninhibited imagination. I could wish he did not suggest Dali as strongly as he does. Occasionally, however, Gattorno puts into his paintings a strength of conviction and a concern with world problems that sets them apart from Dali’s dallyings.” Gattorno spent the years 1919 – 1927 in Europe. He was influenced by a wide variety of old Masters from Giotto, Titian, Veronesé, and Rafael, to contemporaries such as di Chirico and Modigliani. He became enmeshed in the vast tapestry of European art history with all of it’s epochs, movements and schools of thought. He developed a deep and abiding knowledge of symbolic visual language. He immersed himself in the study of style and technique.

Antonio Gattorno perceived himself as a storyteller. He reveals himself as a narrative painter throughout every phase of his work. He exhibits a symbolist proclivity in his first as well as his final paintings.

Critics frequently perceive him as a social crusader with a specific agenda - working to establish a visually unique Cuban national identity. Other critics classify Gattorno as a derivative of more successful contemporaries who never really developed his own style.

Either of these assessments is inaccurate, revealing more about the critics than about the paintings or their author.

This is not to say that Antonio Gattorno had no political message to convey nor does it suggest that he had no singular personal painting style.

Gattorno was primarily a narrative painter, a storyteller working in light, color and image. He was a Symbolist painter in the truest sense.

Gattorno believed that all paintings must be decorative and that all painting must be a meditative, creative process on the part of the artist.

Politics were germane to him solely because being seen as politically relevant added credibility, importance and notoriety to the painter and his work. Making a political statement elevates decorative art to a lofty status where it seems somehow more important than mere adornment.

Gattorno’s participation in the Cuban revolution of 1923 – 1934 was more likely the result of artistic opportunism than of politically motivated idealism.

El Grupo Minorista, the loosely organized collective of artists and writers of which Gattorno was a founding member, viewed his ultimate departure from Cuba as a betrayal of the political activism espoused by El Grupo.

The contentious relationship Gattorno endured with the Cuban academic and political establishment began in his youth and continued throughout his career.

In 1923, his third year in Paris, conservative traditionalists at the Academy of San Alejandro in Havana, accused Gattorno of falling under the corrupting influence of the European Modernists. These charges nearly cost him his stipend.

Professor Leopoldo Romañach, Gattorno’s mentor at San Alejandro interceded on his pupil’s behalf. Romañach declared that it was the young artist’s right to search for any means of expression. He simply needed time and an opportunity to try. Romañach’s intercession insured the stipend remained intact.

Back home in Havana in 1927, Gattorno participated in the landmark exhibit billed as the First Exposition of Modern Art. Held under the auspices of the Association of Painters and Sculptors of Havana, this show marked the definitive transition from the decline of the Cuban Academic tradition to the dominance of Cuban Modernism.

Gattorno acknowledges this time of flux in an essay written for Revista De La Habana. “The respect for art that was once taught is often replaced by devotion to skill. The result is to limit the artist’s desire to create great works of art and to conform by painting “studio heads” according to dogmatic academic convention. This simply is not art. Now, with few rare exceptions, paintings are made without the devotion of the primitive artist… Is this the truth in art? No, it cannot be! The natural world must be gathered and arranged - it must be combined with talent. We must create. The only works of art that deserve respect, are those composed with talent, those done by amassing with color the days of torture that the creation of the work provides us…”

Gattorno’s feud with the stifling conservatism of the Cuban academic establishment continued over the years.

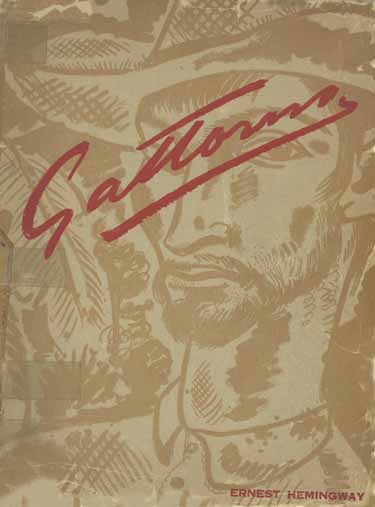

In 1935 Ernest Hemingway acknowledged the conflict in his book, “Gattorno”.

“Gattorno”.

“As things are organized now he could risk his hide a few times for one party or another and if that party won, and had the loot at it’s disposal, he could get his share in an official appointment. But, to see Gattorno, who was made for painting and for nothing else and to ask him to fight is as sensible as using a camel’s hair brush as a bayonet. So he has to go.”

The book was Hemingway’s idea. It was his way of joining in the fray to aid his friend in the ongoing battles with the artistic establishment in Havana.

The National Salon of Havana, which had been held every year since 1916, was controlled by conservative traditional and local academic trends and tastes.

Antonio Gattorno, Carlos Enriquez, Eduardo Abela, Fidelio Ponce, Victor Manuel, Amelia Pelaez or indeed any of the painters now known as the Vanguardia, were not given the recognition merited by their contributions to Cuba’s artistic legacy, in spite of the indisputable quality of their work.

The judging process was widely known to be rife with corruption, favoritism and infighting. The jury was notorious for ignoring the importance of the works of certain artists who were considered innovative or subversive.

Gattorno, writing to Ernest Hemingway in a letter dated June 6 1935, tells his friend, “The painting that won the prize is “Self-portrait and Models”. Everybody said that painting should have won the one thousand-peso prize but the judges were S.O.B.’s and didn’t want to give me the prize, so they split the money into ten one hundred peso awards. Nobody won. I was awarded a five hundred-peso prize, instead of the big prize. And among the winners, I was the first one. This is only a moral victory as in Gorpacio’s play.”

Hemingway, in a letter dated July 3 1935, replied to Gattorno’s complaint. “My dear friend Antonio, Yesterday I returned to Key West and found two of your letters and 50 samples of your book. In reference to the letters, I am deeply sorry that the contest did not work out. We thought that you had won the grand prize a while ago. It is a shame about that contest. Those judges must be jerks.”

The Second National Salon of Havana, held in 1938, dealt with the Vanguardia in the same way it did in 1935. The prize money was divided and split amongst several artists. The title of First Prize winner, assigned this time to Eduardo Abela, was once again only a moral victory ala Gorpacio.

Second place was shared between a half dozen artists including Gattorno, Arche, Enriquez, Manuel, Pelaez and Ponce.

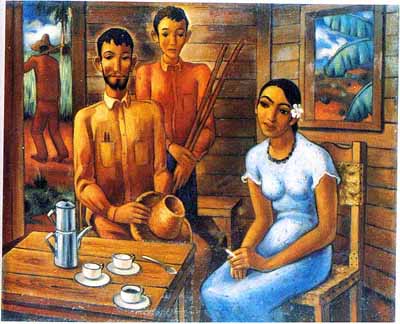

Gattorno’s entry is currently considered one of the superlative representations of Cuban Modern Primitivism.

It is an excellent example of Gattorno’s use of surface and symbol.

“¿Quiere Mas Café Don Nicolas?” appears, superficially, to be a family portrait. A man and woman are seated at a table having coffee while a younger man stands behind them.

A close study of the painting reveals a complex dynamic concealed beneath the tranquil surface of the image.

Gattorno has set the scene to tell a story. He has placed the viewer in the point of view of a landowner named Don Nicolas paying a visit to a guajiro family. We are inside a bohio that has bare walls and traditional Cuban furniture. Behind the younger man is a bench. The man and woman are seated on chairs around a table. Upon the table, sit a coffeepot, a trio of cups and a spoon.

The door behind the older man is open. A guajiro with a hoe over his shoulder walks past outside. Banana leaves fill the open window behind the woman.

The men in the bohio have just come in from the fields. The older one sits in a submissive pose, his hat in his hands. The younger is holding tools. He is the couple’s son or perhaps the man’s brother. He has no hat and no place at the table. Dressed in everyday clothing the gaunt faced men appear to be hardworking farmers suddenly summoned from their regular chores.

Conversely, the woman who is perhaps the wife or sister of the older man, is clad in a pretty dress. There is a flower in her hair. She is dressed for entertaining not for working. She is smoking a cigarette. She is desirable. She is vibrantly young and she blooms like the lush tropical foliage outside. Her expression is serene and reserved. An anticipatory atmosphere of quiet tension pervades the scene.

There are three cups on the table. Only the one poured for Don Nicolas is full. A spoon, having sugared and stirred the cup, lies nearby. The other cups remain glaringly empty.

The cup is a female symbol. The spoon symbolizes male sexuality. A spoon full of sugar stirring a cup is a man inflaming the passions of a woman. The flower in the woman’s hair, a gardenia, is a fertility symbol. A flower worn behind the left ear suggests an experienced or married woman. The burning cigarette, seen symbolically, is a smoking gun implying the aftermath of a sexual encounter. The color of the woman’s dress is another subliminal element. It is not quite white, covered with a floral print, a subtle signal that the maiden herself, while lovely, is not pure.

Even the title is symbolic. “¿Quieres mas café, Don Nicolas?” Evidently the Don has enjoyed a previous cup of coffee. The sentence is in the familiar not the formal style used to address a superior. It is therefore the desirable, vibrant young woman asking the question, not the weary, subservient men. “Nicolas” is not a typical Cuban name, hinting at an ethnic as well as a class difference between the viewer of the scene at the head of the table and the subjects seated below him.

The political and social messages of the painting are now evident.

The plight of these guajiros is poverty and hard work. If they do not toil in the fields they go hungry. The men in power, the landowners, who grow wealthy from the labor of the poor, take whatever they want.

What appears on the surface to be a decorative family portrait is actually a meditatively conceived methodically composed political statement.

“¿Quieres mas café, Don Nicolas?” is a Symbolist painting executed in the genre of Cuban Modernism. It is completely relevant to the contemporary social and political context of Cuba in the 1930s.

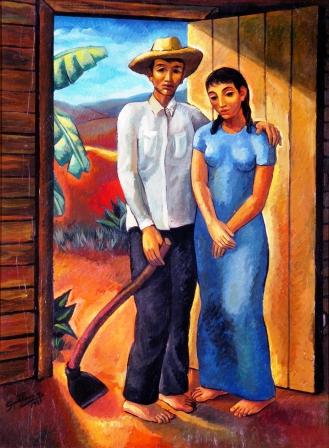

Gattorno’s depictions of the guajiros, their environment and their way of life, marks the debut of the European Modernist aesthetic applied to Cuban themes.

The commonplace, meticulously rendered people, settings and situations revealed in these paintings established Gattorno as the first Cuban artist of his generation to achieve the status of a universal contemporary, transcending his ethnicity and national origins.

John Dos Passos, the author of the groundbreaking trilogy “USA” was sufficiently impressed with Gattorno and his work that he bought a pair of guajiro paintings and commissioned Gattorno to paint the portrait of his wife, Katy. Dos Passos also wrote a piece of lyric prose inspired by Gattorno’s guajiros.

“If you have been looking at Gattorno's paintings you see them as soon as you leave the suburbs of Havana. He seems to have painted them all. You see the men and boys with pale earth colored faces riding their chunky ponies or working in the fields under their broad straw hats or plowing the heavy land with oxen, or scattered, with their machetes in their hands, among the tall white stalks of the royal palms and the ragged intense green of banana patches and the shining cane fields. You see the bare footed frailly built women standing in the doors of their palm thatched huts that have bare earth floors and walls of white washed boards or interwoven palm fiber, and the rickety children and the chickens and the goats and the black pigs dotted over the rolling dry hills under the circling buzzards and the high piled Gulfstream clouds. And always a look of poverty, a certain malarial refinement and sadness and isolation of a transplanted race. They are the guajiros, the poor whites of Cuba, and Gattorno has put them on paper and canvas so well that once you have seen his paintings you continue to see the guajiros through his eyes."

Gattorno’s North American debut occurred in New York City at the Passedoit Gallery in January 1936. It was a critical and commercial success. New York Times art critic Howard Devree, in his review, noted a “Pascin like quality in some of Gattorno’s figures and a broadly, vigorously lyric portrayal of the humble, in a very decorative manner, with much human sympathy in the portrayal."

The Fifteenth International Watercolor Exhibit at the Art Institute of Chicago was held in May 1936. Hundreds of the world’s best painters were involved. The catalog lists the artists by country of origin. Georges Rouault and Jules Pascin, two of Gattorno’s friends and mentors, were members of the French contingent. Diego Rivera and Martin Covarrubias were among the painters representing Mexico. Paul Klee the Swiss surrealist exhibited several works. Antonio Gattorno was the only Cuban artist invited to participate in this prestigious, internationally recognized exhibit.

Gattorno was awarded the Watson F. Blair purchase prize for one of the six paintings he entered. “The White Goat” is the only one of Gattorno’s paintings to belong to a major U.S. museum during his lifetime. It resides in the permanent collection of the Art Institute of Chicago.

Gattorno’s participation in the Cuban revolution of 1923 – 1934 was more likely the result of artistic opportunism than of politically motivated idealism.

El Grupo Minorista, the loosely organized collective of artists and writers of which Gattorno was a founding member, viewed his ultimate departure from Cuba as a betrayal of the political activism espoused by El Grupo.

The contentious relationship Gattorno endured with the Cuban academic and political establishment began in his youth and continued throughout his career.

In 1923, his third year in Paris, conservative traditionalists at the Academy of San Alejandro in Havana, accused Gattorno of falling under the corrupting influence of the European Modernists. These charges nearly cost him his stipend.

Professor Leopoldo Romañach, Gattorno’s mentor at San Alejandro interceded on his pupil’s behalf. Romañach declared that it was the young artist’s right to search for any means of expression. He simply needed time and an opportunity to try. Romañach’s intercession insured the stipend remained intact.

Back home in Havana in 1927, Gattorno participated in the landmark exhibit billed as the First Exposition of Modern Art. Held under the auspices of the Association of Painters and Sculptors of Havana, this show marked the definitive transition from the decline of the Cuban Academic tradition to the dominance of Cuban Modernism.

Gattorno acknowledges this time of flux in an essay written for Revista De La Habana. “The respect for art that was once taught is often replaced by devotion to skill. The result is to limit the artist’s desire to create great works of art and to conform by painting “studio heads” according to dogmatic academic convention. This simply is not art. Now, with few rare exceptions, paintings are made without the devotion of the primitive artist… Is this the truth in art? No, it cannot be! The natural world must be gathered and arranged - it must be combined with talent. We must create. The only works of art that deserve respect, are those composed with talent, those done by amassing with color the days of torture that the creation of the work provides us…”

Gattorno’s feud with the stifling conservatism of the Cuban academic establishment continued over the years.

In 1935 Ernest Hemingway acknowledged the conflict in his book,

“Gattorno”.

“Gattorno”.

“As things are organized now he could risk his hide a few times for one party or another and if that party won, and had the loot at it’s disposal, he could get his share in an official appointment. But, to see Gattorno, who was made for painting and for nothing else and to ask him to fight is as sensible as using a camel’s hair brush as a bayonet. So he has to go.”

The book was Hemingway’s idea. It was his way of joining in the fray to aid his friend in the ongoing battles with the artistic establishment in Havana.

The National Salon of Havana, which had been held every year since 1916, was controlled by conservative traditional and local academic trends and tastes.

Antonio Gattorno, Carlos Enriquez, Eduardo Abela, Fidelio Ponce, Victor Manuel, Amelia Pelaez or indeed any of the painters now known as the Vanguardia, were not given the recognition merited by their contributions to Cuba’s artistic legacy, in spite of the indisputable quality of their work.

The judging process was widely known to be rife with corruption, favoritism and infighting. The jury was notorious for ignoring the importance of the works of certain artists who were considered innovative or subversive.

Gattorno, writing to Ernest Hemingway in a letter dated June 6 1935, tells his friend, “The painting that won the prize is “Self-portrait and Models”. Everybody said that painting should have won the one thousand-peso prize but the judges were S.O.B.’s and didn’t want to give me the prize, so they split the money into ten one hundred peso awards. Nobody won. I was awarded a five hundred-peso prize, instead of the big prize. And among the winners, I was the first one. This is only a moral victory as in Gorpacio’s play.”

Hemingway, in a letter dated July 3 1935, replied to Gattorno’s complaint. “My dear friend Antonio, Yesterday I returned to Key West and found two of your letters and 50 samples of your book. In reference to the letters, I am deeply sorry that the contest did not work out. We thought that you had won the grand prize a while ago. It is a shame about that contest. Those judges must be jerks.”

The Second National Salon of Havana, held in 1938, dealt with the Vanguardia in the same way it did in 1935. The prize money was divided and split amongst several artists. The title of First Prize winner, assigned this time to Eduardo Abela, was once again only a moral victory ala Gorpacio.

Second place was shared between a half dozen artists including Gattorno, Arche, Enriquez, Manuel, Pelaez and Ponce.

Gattorno’s entry is currently considered one of the superlative representations of Cuban Modern Primitivism.

It is an excellent example of Gattorno’s use of surface and symbol.

“¿Quiere Mas Café Don Nicolas?” appears, superficially, to be a family portrait. A man and woman are seated at a table having coffee while a younger man stands behind them.

A close study of the painting reveals a complex dynamic concealed beneath the tranquil surface of the image.

Gattorno has set the scene to tell a story. He has placed the viewer in the point of view of a landowner named Don Nicolas paying a visit to a guajiro family. We are inside a bohio that has bare walls and traditional Cuban furniture. Behind the younger man is a bench. The man and woman are seated on chairs around a table. Upon the table, sit a coffeepot, a trio of cups and a spoon.

The door behind the older man is open. A guajiro with a hoe over his shoulder walks past outside. Banana leaves fill the open window behind the woman.

The men in the bohio have just come in from the fields. The older one sits in a submissive pose, his hat in his hands. The younger is holding tools. He is the couple’s son or perhaps the man’s brother. He has no hat and no place at the table. Dressed in everyday clothing the gaunt faced men appear to be hardworking farmers suddenly summoned from their regular chores.

Conversely, the woman who is perhaps the wife or sister of the older man, is clad in a pretty dress. There is a flower in her hair. She is dressed for entertaining not for working. She is smoking a cigarette. She is desirable. She is vibrantly young and she blooms like the lush tropical foliage outside. Her expression is serene and reserved. An anticipatory atmosphere of quiet tension pervades the scene.

There are three cups on the table. Only the one poured for Don Nicolas is full. A spoon, having sugared and stirred the cup, lies nearby. The other cups remain glaringly empty.

The cup is a female symbol. The spoon symbolizes male sexuality. A spoon full of sugar stirring a cup is a man inflaming the passions of a woman. The flower in the woman’s hair, a gardenia, is a fertility symbol. A flower worn behind the left ear suggests an experienced or married woman. The burning cigarette, seen symbolically, is a smoking gun implying the aftermath of a sexual encounter. The color of the woman’s dress is another subliminal element. It is not quite white, covered with a floral print, a subtle signal that the maiden herself, while lovely, is not pure.

Even the title is symbolic. “¿Quieres mas café, Don Nicolas?” Evidently the Don has enjoyed a previous cup of coffee. The sentence is in the familiar not the formal style used to address a superior. It is therefore the desirable, vibrant young woman asking the question, not the weary, subservient men. “Nicolas” is not a typical Cuban name, hinting at an ethnic as well as a class difference between the viewer of the scene at the head of the table and the subjects seated below him.

The political and social messages of the painting are now evident.

The plight of these guajiros is poverty and hard work. If they do not toil in the fields they go hungry. The men in power, the landowners, who grow wealthy from the labor of the poor, take whatever they want.

What appears on the surface to be a decorative family portrait is actually a meditatively conceived methodically composed political statement.

“¿Quieres mas café, Don Nicolas?” is a Symbolist painting executed in the genre of Cuban Modernism. It is completely relevant to the contemporary social and political context of Cuba in the 1930s.

Gattorno’s depictions of the guajiros, their environment and their way of life, marks the debut of the European Modernist aesthetic applied to Cuban themes.

The commonplace, meticulously rendered people, settings and situations revealed in these paintings established Gattorno as the first Cuban artist of his generation to achieve the status of a universal contemporary, transcending his ethnicity and national origins.

John Dos Passos, the author of the groundbreaking trilogy “USA” was sufficiently impressed with Gattorno and his work that he bought a pair of guajiro paintings and commissioned Gattorno to paint the portrait of his wife, Katy. Dos Passos also wrote a piece of lyric prose inspired by Gattorno’s guajiros.

“If you have been looking at Gattorno's paintings you see them as soon as you leave the suburbs of Havana. He seems to have painted them all. You see the men and boys with pale earth colored faces riding their chunky ponies or working in the fields under their broad straw hats or plowing the heavy land with oxen, or scattered, with their machetes in their hands, among the tall white stalks of the royal palms and the ragged intense green of banana patches and the shining cane fields. You see the bare footed frailly built women standing in the doors of their palm thatched huts that have bare earth floors and walls of white washed boards or interwoven palm fiber, and the rickety children and the chickens and the goats and the black pigs dotted over the rolling dry hills under the circling buzzards and the high piled Gulfstream clouds. And always a look of poverty, a certain malarial refinement and sadness and isolation of a transplanted race. They are the guajiros, the poor whites of Cuba, and Gattorno has put them on paper and canvas so well that once you have seen his paintings you continue to see the guajiros through his eyes."

Gattorno’s North American debut occurred in New York City at the Passedoit Gallery in January 1936. It was a critical and commercial success. New York Times art critic Howard Devree, in his review, noted a “Pascin like quality in some of Gattorno’s figures and a broadly, vigorously lyric portrayal of the humble, in a very decorative manner, with much human sympathy in the portrayal."

The Fifteenth International Watercolor Exhibit at the Art Institute of Chicago was held in May 1936. Hundreds of the world’s best painters were involved. The catalog lists the artists by country of origin. Georges Rouault and Jules Pascin, two of Gattorno’s friends and mentors, were members of the French contingent. Diego Rivera and Martin Covarrubias were among the painters representing Mexico. Paul Klee the Swiss surrealist exhibited several works. Antonio Gattorno was the only Cuban artist invited to participate in this prestigious, internationally recognized exhibit.

Gattorno was awarded the Watson F. Blair purchase prize for one of the six paintings he entered. “The White Goat” is the only one of Gattorno’s paintings to belong to a major U.S. museum during his lifetime. It resides in the permanent collection of the Art Institute of Chicago.

Gattorno began to divide his time between Cuba and the U.S. spending increasingly more time in New York City. He participated in solo and group exhibitions. He was given the commission to paint a mural at the Bacardi Company Headquarters in the newly constructed Empire State Building late in 1937. The mural titled “Waiting For The Coffee” was completed in January of 1938.

Gattorno received excellent critical recognition in the U.S. and plenty of work. He’d been growing disillusioned over his battles with the conservative Cuban academic establishment. He was getting neither the recognition nor the work necessary to support his career.

Hemingway best expresses Gattorno’s motivation to leave Cuba in the following excerpt from his essay.

“Cuba is even more a place to leave than a place to return to. Why is it a place to leave? Because a painter cannot make his living there, because he can never see any great painting to wash his mind clear and encourage his heart, because if he gets to be a great painter no none would ever know it nor would they buy enough of his paintings for him to able to eat. There is no one there even who can photograph a painting properly and no one to reproduce it as it should be reproduced. Why is it a place to come back to? Because you are born there and every artist owes it to the place he knows best to either destroy it or perpetuate it. Now he must work. He does not know how much he must work because he can see that it is all in a single picture when he paints that picture. But to live you must, if not repeat, insist. He must go on insisting. He will never be bankrupt because you cannot bankrupt pure skill. And no one owes any thing to the world. But I would like to see him paint much more because while he can put it all in one picture he can put it all in again and there will be other things. It is like hauling through the same part of the sea with a net with different dimensions of mesh. But if he will not change his net and wants to go to other seas why let him go. And when he returns again there will be other fish in these waters that will not go through his mesh. The thing for him to do is to paint, wherever he is. But to do that he has to eat, to buy his materials and have a place to work. As things are organized now he could risk his hide a few times for one party or another and if that party won, and had the loot at its disposal, he could get his share in an official appointment. But to see Gattorno, who was made for painting and for nothing else, and to ask him to fight, is as sensible, economically and tactically, as to use a camel’s hair brush for a bayonet. So he has to go. The trouble with people who do things perfectly as they go along is that they do not realize that they improve. Gattorno can be much better than he is although he can never be any better than he is at the time. He must go on and he must paint…”

Gattorno did go on and he did paint, in the U.S. not in Cuba. His decision to move to New York City, based solely on creative and career considerations, was seen by many in Havana as a desertion by one of their most influential artistic leaders.

The single most significant act of retribution for Gattorno’s perceived abandonment of his role as a politically active Cuban painter was his exclusion from the 1944 MOMA Exhibit, "Cuban Painting of Today". It was one of the most important exhibitions of Cuban modern art ever assembled. Although Gattorno and Wifredo Lam are featured in the exhibition catalog, neither one had works presented in the show. Each artist had a poor relationship with Jose Gomez-Sicre, the Cuban art critic (and later director of the museum of the OAS) who assembled the exhibit and acted as liaison for Alfred Barr, the director of MoMA and curator of the exhibit.

Gomez-Sicre had personal feuds with both Gattorno and Lam but could not deny their place in Cuba's Modern Art movement. He did deny them inclusion in this prestigious event. Although Gattorno is featured in the catalog, the paintings shown are at least three years old. There are no color pictures of his work, which since 1939 had been delving ever more deeply into the realm of surrealistic romanticism.

The final words of Gomez-Sicre's commentary on Gattorno resound with feelings of betrayal over the artist's ex-patriation. "For the last six years Gattorno has lived in the United States and as a result his connection with the group of modern painters in Cuba has now become rather remote." There is an undertone of resentment in these words; they seem to be a rebuke, admonishing Gattorno for abandoning his country and his compatriots.

In a letter to Barr addressed March 5, 1943, Gattorno protested his exclusion from the exhibit. "I regret that I was not in Cuba at the time you visited there, but the mere fact that I was absent, living here in New York City, does not alter the fact that I am also a Cuban artist and I daresay, one who has honored the name of Cuba more than any other living Cuban artist of today. I do not aspire to have the Museum of Modern Art purchase one of my paintings because I am well aware of the fact that these appropriations are made methodically, however, I would appreciate the opportunity of participating in this Cuban show by lending one of my paintings selected by the museum. I believe that if the museum is interested in the record of the artists it exhibits, my record will justify the privilege which I am requesting."

Over the years, Gomez-Sicre often spoke dismissively of Gattorno, remarking that his arrogance canceled out the esthetic importance of his work. And Gattorno's letter to Barr, while certainly justified, does have a defiant and arrogant tone. But Gattorno's assessment of his place and his importance in Cuba's modern art movement is accurate and not simply the ranting of an egomaniac.

Antonio Gattorno underwent a profound spiritual and creative metamorphosis in the late 1930s. This personal and painterly evolution continued throughout the 1940s. He immersed himself in his life and his work. He produced many of his most important paintings during this time. He took Hemingway’s advice and relocated to New York City permanently in 1939. There he met Isabel Cabral and married her in 1940. He exhibited internationally as an American painter. Gattorno did not return to Cuba for an exhibit until 1952.

Gattorno received excellent critical recognition in the U.S. and plenty of work. He’d been growing disillusioned over his battles with the conservative Cuban academic establishment. He was getting neither the recognition nor the work necessary to support his career.

Hemingway best expresses Gattorno’s motivation to leave Cuba in the following excerpt from his essay.

“Cuba is even more a place to leave than a place to return to. Why is it a place to leave? Because a painter cannot make his living there, because he can never see any great painting to wash his mind clear and encourage his heart, because if he gets to be a great painter no none would ever know it nor would they buy enough of his paintings for him to able to eat. There is no one there even who can photograph a painting properly and no one to reproduce it as it should be reproduced. Why is it a place to come back to? Because you are born there and every artist owes it to the place he knows best to either destroy it or perpetuate it. Now he must work. He does not know how much he must work because he can see that it is all in a single picture when he paints that picture. But to live you must, if not repeat, insist. He must go on insisting. He will never be bankrupt because you cannot bankrupt pure skill. And no one owes any thing to the world. But I would like to see him paint much more because while he can put it all in one picture he can put it all in again and there will be other things. It is like hauling through the same part of the sea with a net with different dimensions of mesh. But if he will not change his net and wants to go to other seas why let him go. And when he returns again there will be other fish in these waters that will not go through his mesh. The thing for him to do is to paint, wherever he is. But to do that he has to eat, to buy his materials and have a place to work. As things are organized now he could risk his hide a few times for one party or another and if that party won, and had the loot at its disposal, he could get his share in an official appointment. But to see Gattorno, who was made for painting and for nothing else, and to ask him to fight, is as sensible, economically and tactically, as to use a camel’s hair brush for a bayonet. So he has to go. The trouble with people who do things perfectly as they go along is that they do not realize that they improve. Gattorno can be much better than he is although he can never be any better than he is at the time. He must go on and he must paint…”

Gattorno did go on and he did paint, in the U.S. not in Cuba. His decision to move to New York City, based solely on creative and career considerations, was seen by many in Havana as a desertion by one of their most influential artistic leaders.

The single most significant act of retribution for Gattorno’s perceived abandonment of his role as a politically active Cuban painter was his exclusion from the 1944 MOMA Exhibit, "Cuban Painting of Today". It was one of the most important exhibitions of Cuban modern art ever assembled. Although Gattorno and Wifredo Lam are featured in the exhibition catalog, neither one had works presented in the show. Each artist had a poor relationship with Jose Gomez-Sicre, the Cuban art critic (and later director of the museum of the OAS) who assembled the exhibit and acted as liaison for Alfred Barr, the director of MoMA and curator of the exhibit.

Gomez-Sicre had personal feuds with both Gattorno and Lam but could not deny their place in Cuba's Modern Art movement. He did deny them inclusion in this prestigious event. Although Gattorno is featured in the catalog, the paintings shown are at least three years old. There are no color pictures of his work, which since 1939 had been delving ever more deeply into the realm of surrealistic romanticism.

The final words of Gomez-Sicre's commentary on Gattorno resound with feelings of betrayal over the artist's ex-patriation. "For the last six years Gattorno has lived in the United States and as a result his connection with the group of modern painters in Cuba has now become rather remote." There is an undertone of resentment in these words; they seem to be a rebuke, admonishing Gattorno for abandoning his country and his compatriots.

In a letter to Barr addressed March 5, 1943, Gattorno protested his exclusion from the exhibit. "I regret that I was not in Cuba at the time you visited there, but the mere fact that I was absent, living here in New York City, does not alter the fact that I am also a Cuban artist and I daresay, one who has honored the name of Cuba more than any other living Cuban artist of today. I do not aspire to have the Museum of Modern Art purchase one of my paintings because I am well aware of the fact that these appropriations are made methodically, however, I would appreciate the opportunity of participating in this Cuban show by lending one of my paintings selected by the museum. I believe that if the museum is interested in the record of the artists it exhibits, my record will justify the privilege which I am requesting."

Over the years, Gomez-Sicre often spoke dismissively of Gattorno, remarking that his arrogance canceled out the esthetic importance of his work. And Gattorno's letter to Barr, while certainly justified, does have a defiant and arrogant tone. But Gattorno's assessment of his place and his importance in Cuba's modern art movement is accurate and not simply the ranting of an egomaniac.

Antonio Gattorno underwent a profound spiritual and creative metamorphosis in the late 1930s. This personal and painterly evolution continued throughout the 1940s. He immersed himself in his life and his work. He produced many of his most important paintings during this time. He took Hemingway’s advice and relocated to New York City permanently in 1939. There he met Isabel Cabral and married her in 1940. He exhibited internationally as an American painter. Gattorno did not return to Cuba for an exhibit until 1952.

Antonio Gattorno was fifty-seven years old in 1961. Three decades had passed since his involvement in the volatile Cuban political scene of the 1930s. He was well versed in the power of imagery and in the machinations of the political process in both Cuba and the United States.

Friends and family recall that he was worldly and sophisticated in his understanding of art, of politics and of human nature. He spoke eloquently about each. His knowledge came from firsthand experience.

In 1959, during the early days of Fidel Castro’s revolution, Gattorno was optimistic for Cuba’s future. He initially admired what appeared to be Castro’s strength. He believed that Castro had liberated Cuba from a totalitarian regime.

But it didn’t take long for the artist to decide that Castro was a dishonest egomaniac who had betrayed the Cuban people in general, and Gattorno’s family in particular. In 1960 when Castro was in New York City, arrangements were made for Gattorno to meet him.

In newspaper interviews and in conversations with family and friends, Gattorno spoke of that meeting. He recounted how Castro had kept him waiting for hours and then insulted him. “You should return home to Cuba where you belong. I can help you to become a famous painter” said Castro. Gattorno replied that he was already famous and would return to Cuba, “When you are no longer there.”

“La Navidad” was painted just one year after the ill-fated meeting between Gattorno and Castro. Superficially it tells the familiar story of the Holy Family and the birth of Jesus.

Friends and family recall that he was worldly and sophisticated in his understanding of art, of politics and of human nature. He spoke eloquently about each. His knowledge came from firsthand experience.

In 1959, during the early days of Fidel Castro’s revolution, Gattorno was optimistic for Cuba’s future. He initially admired what appeared to be Castro’s strength. He believed that Castro had liberated Cuba from a totalitarian regime.

But it didn’t take long for the artist to decide that Castro was a dishonest egomaniac who had betrayed the Cuban people in general, and Gattorno’s family in particular. In 1960 when Castro was in New York City, arrangements were made for Gattorno to meet him.

In newspaper interviews and in conversations with family and friends, Gattorno spoke of that meeting. He recounted how Castro had kept him waiting for hours and then insulted him. “You should return home to Cuba where you belong. I can help you to become a famous painter” said Castro. Gattorno replied that he was already famous and would return to Cuba, “When you are no longer there.”

“La Navidad” was painted just one year after the ill-fated meeting between Gattorno and Castro. Superficially it tells the familiar story of the Holy Family and the birth of Jesus.

Beneath the surface lies a carefully crafted visual metaphor, a subtle, enigmatic political commentary on the birth of a nation.

The newborn child is in a manger on the floor between his parents. Mary wears red robes with a blue veil as she knits a small piece of white cloth. Above her head shines a single, six pointed, star. Joseph holds a file and a sickle. A hammer lies at his feet. A pitchfork, ceramic vessels and a heavily laden beast of burden imply agricultural toil and industrial production.

Mary's face is calm, her expression serene. The infant lies vulnerable at her feet. Mary's blood red skirt flows between her legs symbolizing the long and difficult birth of the new Cuba. The man with his tools and his politics is focused on his work. Mary and the child are radiant, luminescent, portending a bright and hopeful future for the nascent nation.

Gattorno’s “La Navidad” poses symbolic, metaphorical questions of a political and social nature.

Will the newly born child be clad in the red, white and blue ideals of capitalist freedom as knitted together by the mother of democracy? Or will the infant bear the tools of collective labor under the yoke of its ideological father the communist state?

Gattorno, always a shrewd and calculating man, was more pragmatic than he was idealistic. The answers to those questions were not as important to him as was the painting asking them. He was far more interested in art than in politics.

Gattorno considered politics and popular culture, religion and spirituality as nothing less than ideal sources of subject matter. If they happened to enhance the social and historic value of his works, so be it.

He chose to eschew political activity, social reform or religious debate, devoting himself instead to gathering and arranging elements of the natural world, combining them with talent to explore, evolve and express his own unique artistic vision.

Gattorno steadfastly maintained his creative integrity even at the cost of commercial success. Evidence of this devotion to his painterly principles is the substantial body of work he produced over the course of a career that spanned more than half a century.

Primitive, surreal or symbolic the life and work of Antonio Gattorno remain versatile, innovative and enigmatic.

The newborn child is in a manger on the floor between his parents. Mary wears red robes with a blue veil as she knits a small piece of white cloth. Above her head shines a single, six pointed, star. Joseph holds a file and a sickle. A hammer lies at his feet. A pitchfork, ceramic vessels and a heavily laden beast of burden imply agricultural toil and industrial production.

Mary's face is calm, her expression serene. The infant lies vulnerable at her feet. Mary's blood red skirt flows between her legs symbolizing the long and difficult birth of the new Cuba. The man with his tools and his politics is focused on his work. Mary and the child are radiant, luminescent, portending a bright and hopeful future for the nascent nation.

Gattorno’s “La Navidad” poses symbolic, metaphorical questions of a political and social nature.

Will the newly born child be clad in the red, white and blue ideals of capitalist freedom as knitted together by the mother of democracy? Or will the infant bear the tools of collective labor under the yoke of its ideological father the communist state?

Gattorno, always a shrewd and calculating man, was more pragmatic than he was idealistic. The answers to those questions were not as important to him as was the painting asking them. He was far more interested in art than in politics.

Gattorno considered politics and popular culture, religion and spirituality as nothing less than ideal sources of subject matter. If they happened to enhance the social and historic value of his works, so be it.

He chose to eschew political activity, social reform or religious debate, devoting himself instead to gathering and arranging elements of the natural world, combining them with talent to explore, evolve and express his own unique artistic vision.

Gattorno steadfastly maintained his creative integrity even at the cost of commercial success. Evidence of this devotion to his painterly principles is the substantial body of work he produced over the course of a career that spanned more than half a century.

Primitive, surreal or symbolic the life and work of Antonio Gattorno remain versatile, innovative and enigmatic.